The EU can regulate not only through legally binding instruments such as treaties, regulations, and directives—or “hard law”—but also through the various recommendations, opinions, communications, notices, and guidelines issued by the European Commission, known as “soft law.” Contrary to the rules of “hard law”, those of “soft law” lack legally binding force—but not legal effects!

The increasing recourse to soft law instruments in European courts

European soft law dates to 1962, when the “Christmas notices” were issued, dealing with commercial agents and intellectual property. Yet the first mention of soft law in Courts occurred only in the 1980s, and has greatly increased over the last decade. Why so?

• the context has recently been favorable to soft law: the White Paper on European governance in 2001 suggested that non-binding legal instruments should be coherently combined with hard legislation.

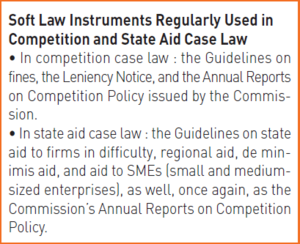

• the issuing of two soft law instruments in competition law. The Guidelines on fines and the Notice on Leniency notice both directly shape the way that the Commission fixes fines or exonerates whistle blowers. Applicants often make recourse to these particular soft law instruments. Hence, “the growing number of soft law instruments augments the likelihood of litigants bringing arguments based on these type of measures,” says Oana Stefan. Moreover, this tendency will probably soon reach national courts as well. Regulation 1/2003 calls on the courts of the Member States to handle European competition cases. This domain is thus no longer the exclusive domain of European Courts. The number of situations in which national courts are asked to grapple with European soft law is therefore likely to increase.

How are soft law instruments used?

The Grimaldi case in 1989 was a turning point: Salvatore Grimaldi, the plaintiff, suffered from an occupational disease that wasn’t listed in the Belgian Fonds des maladies professionnelles, but was in the European list, along with a specific EU recommendation for Member States to introduce it into their national lists. The Court “took into consideration” this EU recommendation in its decision. It’s a part of European norms: European Courts insist on the distinction between “rules of law(règles de droit) and rules of practice (règles de conduite).” Their decisions cannot be directly based on soft law. “For instance, the Court always stresses the fact that the guidelines do not constitute the legal basis that determines the amount of fines,” says Oana Stefan.

Furthermore, soft law cannot depart from hard law or previous case law: “The Courts treat soft law as an integral part […] of the body of European norms ...” Soft law is quoted to reinforce an argument, in footnotes, as part of the description of the legal framework invoked in a case. The creation of legal hybrids : Using the hybridity model recently developed in EU legal studies, Oana Stefan shows that “Courts have created ex post hybridity, the merging of soft and hard law that was not consciously planned by regulators, but evolved as a response to existing needs during the application of norms to concrete cases.” The Courts can decide to apply soft law, combining it with principles such as human rights, legal certainty, legitimate expectations, etc. … This combination of soft and constitutional principles produces legal hybrids.

What does this legal practice change?

• On the individual level: for European courts, the mere existence of notices creates legitimate expectations: for instance, companies “are entitled to assume that they are allowed to conclude agreements” satisfying the de minimis notice criteria.

• On the Commission level: It has to respect its own notices and guidelines. The courts have even annulled decisions from the Commission because they failed to comply with soft law. To depart from notices, it has to justify its action “in a satisfactory way.”

• On national courts: With their new role in competition law, “it would be difficult for national courts to ignore the soft law instruments in which the European Commission explains and further develops certain provisions of hard law,” notes Oana Stefan.

• On hard law: soft law can be used to grant direct effect to a hard law provision. One notice, for example, enables individuals to bring competition cases in front of their national courts and invoke EU hard law. Moreover, soft law can be used as a criterion to review an act of hard law: In BASF, Stefan explains, a decision of the Commission was considered to be ”vitiated of illegality” because of the misapplication of the Leniency Notice.