Rankings have become crucial regulatory devices to put “soft” regulatory pressures on corporations with the aim of influencing their environmental and social policies and practices. HEC Professor Afshin Mehrpouya in collaboration with Dr Rita Samiolo of King’s College have studied the development of what they term “regulatory rankings” in areas ranging from healthcare to nutrition, and mining. This view from within has given them a unique perspective on the issues that arise when creating and interpreting rankings; some of these issues will be examined in this article.

1. Rankings move regulation from public arenas to private ones

Many organisations that create rankings, from for-profit media outlets (such as the Financial Times Business School rankings, or US News Law School rankings) to NGOs (such as the World Economic Forum, which develops wide ranging environmental and social rankings, or the Access to Medicine Foundation), Think Tanks (such as the Fraser Institute’s school rankings), universities (such as Shanghai Jiao Tong University, which develops the Academic Ranking of World Universities), can be viewed as “petty sovereigns”.

Who should set the rules about the responsibilities of corporations? How can they be guided towards making decisions that benefit society as a whole?

This is a notion used by philosopher Judith Butler to refer to non-state/public organisations that play the role of the state without a public mandate. As a result, debates about matters of public concern tend to shift from public arenas, to private ones.

All such rankings that seek to address matters of public good/concern have to emulate the “public” in private arenas by: organizing consultation processes, managing the problem of inclusion of all voices, especially those of the beneficiaries who are frequently powerless, and ill-equipped to be part of such consultations, and dealing with sustained conflict among stakeholders.

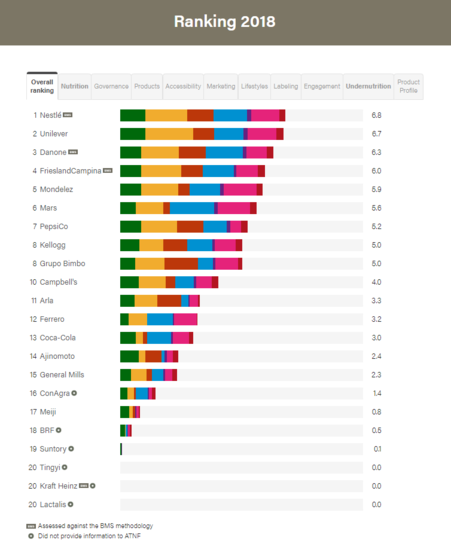

The Access to Nutrition Index ranks large nutrition companies on their approach to malnutrition and undernutrition.

2. Rankers are frequently small and fragile organizations

Unlike states, rankers are frequently small and “fragile organisations fighting for resources and legitimacy, with major implications for the way they operate” Mehrpouya explains. Especially in the first few years of their operation, this fragility makes them vulnerable to intimidation and potentially “regulatory capture” by powerful actors. As they gain legitimacy and build regulatory authority in the field, they can become more assertive and less prone to such intimidation.

It is important to be cautious about the implications of such fragility for the soft regulatory regimes that such rankings sustain.

3. Rankings frequently focus more on “positive practices” to build “soft” power

As the organisations that build rankings don’t have the sanctioning power of the state, they have to rely on motivational and reputational pressure. This has a number of implications.

In order to be effective, regulatory rankings require the consent and participation of their targets and they need to induce a competitive game around the issues of public concern at stake in the ranking.

To attain this response, such rankings frequently focus more on positive behaviour (for example innovation in environmental and social initiatives) and less on exposing and emphasizing problematic behaviour or malpractices (such as ethical breaches and environmental and social damage).

It is important to pay attention to how the need for “buy-in” by targets can influence the emphasis and focus of the ranking exercise.

4. Rankings need to balance the ambition to include all stakeholders with the need to focus on actors with power over the target firms

For reputational pressure to be effective, rankings have to make sure that they are taken seriously by the actors with most power and legitimacy in the eyes of the target companies.

For rankings to be effective, such actors – including investors but also regulators and customers – have to use the ranking device in their decision-making. For a business school, these crucial third parties would be primarily students or donors, for a pharmaceutical company these would be investors, large NGOs and the purchasing agencies of some of the larger governments in the world.

Ranking devices tend to focus more on such stakeholders with power over their targets, which can distract the ranker from engaging and giving voice to other concerned actors who do not have such power.

Responsible Mining Index is a ranking that ranks the environmental and social responsibility of large mining companies.

5. Rankings have to compromise between fairness, reliability and impact on targets

Ranking involves various political pressures on the quantification process, or what Mehrpouya & Samiolo call “the politics of variability”.

For example, for certain performance indicators used in ranking, the differences among companies can at times be very small or immaterial. Regardless, rankings need to rank and generate a discrete order, so they have to squeeze difference from their data even when the performance of targets is hard to differentiate. This is while civil society actors frequently prefer rankings which have a lower average score, so that they can use it to put accountability pressures on companies.

Despite these balancing efforts, however, rankings are frequently more successful in enticing competition among those companies on top. Different rankings have been devising different approaches to deal with this challenge. For example, some have started issuing sub-rankings of the most improved companies, trying to give also the bottom companies in the ranking an incentive to stand out in a positive way.

Ultimately, this means rankers have to strike a trade-off between fairness, attempts at representing the underlying social realities, and ensuring a ranking device has an impact on the targets.

Ultimately, rankers have to strike a trade-off between fairness, attempts at representing the underlying social realities, and ensuring a ranking device has an impact on the targets.

The “Access to Medicine Index” ranks the pharmaceutical companies with regards to provision of access to safe and affordable medicines in poor countries.

6. Rankings need to construct comparability among targets, and distil complex issues into a single number

Indexes and rankings must summarise very complex entities into one single number in order to create competition around that number. This involves a range of assumptions – entities must be assumed to be comparable with one another.

Companies have different business models, geographical footprints, and product ranges. Constructing comparability among such diverse entities is a big and highly political challenge. Companies constantly lobby to have the ranking include the areas in which they out-compete other companies.

The rankers have to engage with such demands, while attempting to maintain consistency in their methodologies and territory of measurement. Dealing with differences among targets and the tensions around comparability are central preoccupations for all rankings.

According to Mehrpouya & Samiolo, “rankings are part of an expanding system of governance where competition and reputational pressures have become central to the regulation of corporations”. Research by Mehrpouya & Samiolo shows the need to foreground rankings’ production process and institutional structures, and to evaluate how reliance on competition skews regulatory efforts and even the definition of problems and solutions in areas of public concern such as education, healthcare, climate change and nutrition.