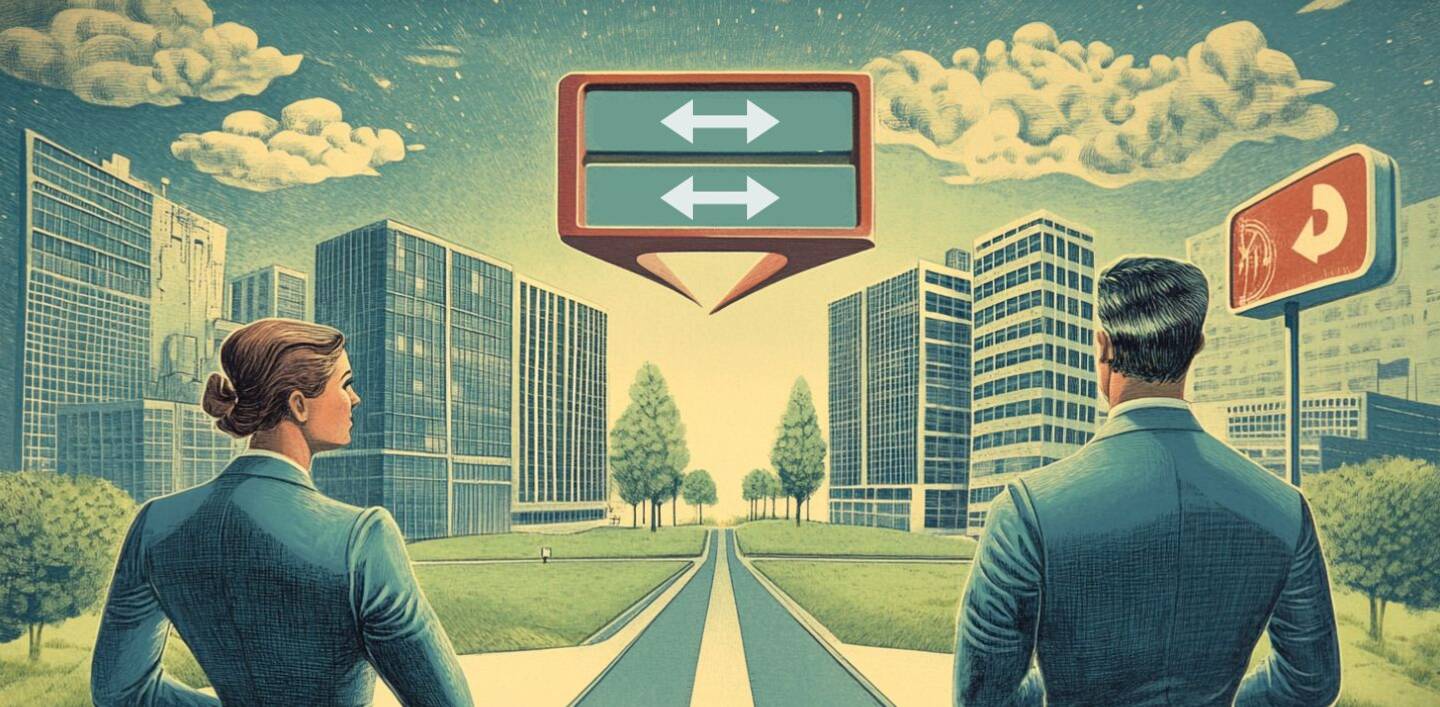

- Companies often delay training because they risk seeing rival firms poach their trained employees.

- So, job mobility affects incentives in training workers. This timing margin changes who is trained, and when.

- Context matters (US vs Europe): lower-mobility markets like Europe can favor firms’ investments (as workers are then less likely to leave).

Across rich economies, job-to-job moves are a central engine of wage growth and productivity reallocation. But mobility also raises the risk that rivals “poach” freshly trained workers. Empirically, firms provide less training where poaching pressure is high (e.g., in dense, highly competitive labor markets). And in the U.S., roughly one in five workers is currently covered by non-compete agreements (and about two in five have been covered at some point), highlighting how pervasive employer attempts are to protect training investments amid mobility. The regulatory stance is in flux: the 2024 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) rule banning most non-competes was blocked and remains tied up in litigation and policy shifts. Giacomo Rostagno explains that getting the timing and rules right is a big, economy-wide question, not a niche HR issue.

You find that competition doesn’t just affect how much firms train, but also when they do it. Can you explain this timing effect in simple terms?

Giacomo Rostagno: Indeed, in my recent paper, I explore a fundamental question: why do firms often wait to provide general training?

My main finding is that labor market competition shapes not only the incentives of firms to train their young workers, but also the timing of that investment. If workers can move into better jobs easily, they are more likely to invest in their own skills. But this same mobility can make firms hesitant to invest in their employees, fearing they might leave soon after receiving costly training. As a result, firms may strategically delay training to avoid losing their investment to competitors. While this delay is not random, it is a cost-benefice response to the competitive pressures. This deferral reduces workers’ incentives to invest in themselves, especially young graduates, ultimately lowering overall productivity.

This is particularly relevant today. For example, JP Morgan recently prohibited their graduate hires from accepting future-dated jobs with competitors, limiting worker mobility. This raises key questions about how such policies impact incentives to invest in workers.

Labor mobility varies a lot between the U.S. and EuropeWhat lessons does your research offer for each side of the Atlantic?

GR: My research can help highlight how differences in labor mobility shape the impact of non-compete agreements on workers and firms across the Atlantic.

In Europe, where labor markets are generally less mobile, workers already face barriers to changing jobs. Non-compete agreements further restrict their opportunities, reducing their chances of moving into more productive and higher-paying positions. This limited mobility means such agreements can trap workers in less favorable roles, compounding the difficulties they face in advancing their careers.

In contrast, in the United States, mobility is much higher - workers switch jobs frequently and competition is more intense. Here, the risks are different: excessive turnover can discourage firms from investing in training, since employees may leave quickly. In this environment, carefully limiting non-compete agreements could reduce pressure, balancing mobility with stability and creating conditions for firms to invest more in workers’ skills.

Ultimately, the policy challenge is not just about incentives in isolation, but about how mobility dynamics differ across contexts. What helps protect workers and promote investment in one setting may backfire in another.

Policymakers are debating non-compete bans worldwide. What should they consider?

GR: You can’t have a one-size-fits-all policy. Competition authorities often assume these agreements are bad. But that’s not always true; it depends on the context. Labor markets vary. France is not the U.S., so before banning or approving non-compete clauses, policymakers need to understand the dynamics of each market.

You’ll soon be bringing your research into practice at RBB Economics. How do you see academic ideas influencing real-world policy?

GR: Conferences are key. We present our work to academics to receive feedback, and meet professionals from antitrust authorities or economic institutions. These are opportunities to influence how policies are designed. From September onwards, I will be joining RBB Economics in Brussels as an Associate. RBB is a consulting firm that specializes in competition economics. That way, I can bring research insights directly into policy discussions.

At the time of this publication, Giacomo Rostagno had started to work at RBB in Brussels and shared his first impressions: “For the moment, I am really happy. I haven't started to work on a specific project yet, but I am going through the economist training.”