Data Protection Law’s Leap into the 21st Century

The European Union brought its General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR, into force on May 25, 2018, 20 years after the United Kingdom enacted its previous legislation, Data Protection Act, DPA. The GDPR is essentially an update of an act designed to protect personal data stored electronically and providing legal rights to individuals who have their data “processed”. But what impact does it have on institutional media? This question was at the heart of the presentation by David Erdos, Senior Lecturer in Law and the Open Society at the University of Cambridge.

In November 2018, Erdos was invited to discuss his work at the second research seminar jointly organized by the HEC Law Department and Sciences Po. After the two-hour session, the Deputy Director of the Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Law shared his insight with HEC Paris.

The GDPR is a very new kid on the block, having only been implemented in May. You are a researcher exploring how data protection affects the flow of information. Given this short lapse of time, how easy is it to analyze its intersection with the right to privacy, freedom of expression and freedom of research?

David Erdos: It’s too early to tell with exactitude what impact GDPR will have. But you must remember that we’ve had around 40 years of experience of European Data Protection measures, going back to the world’s first law in 1973, enacted in Sweden. Then, there was the convention from the Council of Europe in the early 1980s and the Data Protection directive in place since the late Nineties. So, from all that we do know roughly what data protection is, as well as its challenges for Europe. The GDPR has a lot of family resemblances with the past. Nevertheless, it brings new things to the table to answer massively developing data processing. Unfortunately, there are very scarce resources to answer challenges posed by the ever-increasing gap between laws on the books and laws in reality. You can predict these general patterns from what is going on on-the-ground and what’s happened in the past. But, in terms of specifics and details in the GDPR, yes, I think there is a lot we don’t know.

The U.K. is a particular focus in your research. In this region, one notes wide exemptions to data protection. The media, for example, does not need consent to process personal data, according to Data Protection Advisor Jon Baines. How does this reflect the challenges in implementing the GDPR?

David Erdos: In terms of implementation, the GDPR leaves it up to the discretion of member states and so we see a very, very, mixed picture, much like in the past. You have countries like Italy and Greece where data protection has always played a strong role in terms of media regulation. There are other countries, especially in northern Europe where it’s played much less of a role – probably including the U.K., but it’s a complex case.

It’s true that data protection legislation in the U.K. has not fundamentally changed those tests which remain very liberal towards the media. But it’s also true that the latest legislation puts in place new provisions for the regulator to develop a code of conduct here, to monitor the media in terms of their levels of compliance, to publish guidance on redress and also for the government to monitor how effective self-regulation redress is. I don’t think we’ll see immediate changes but, in the medium term, such changes could come.

Another point to make is that more private parties in the U.K. are seeking to raise data protection arguments in courts. There is more awareness of data protection in relation to the media than there was ten years ago. It would be interesting to see if this is a common trend in Europe.

In terms of media awareness, there are two points to make. Firstly, the DPA sits alongside a number of other legal frameworks such as defamation and the tort of the misuse of private information within the common law. Data protection is just one element. Secondly, within quality press institutions there is more concern to at least explore data protection issues as regards accuracy, the right to be forgotten and news archives. Are they putting processes in place to respond to the regulator’s guidance concerning journalism? To some extent, yes, and they certainly are watching these developments with interest - but also with concern. Tabloids generally sit at even greater variance with data protection and might face even greater challenges in the future.

I interact regularly with journalists on the ground and I can say this increased focus on data protection, this awareness that data regulators will be involved in drafting a code of conduct and in monitoring it and the increasing number of court cases (particularly in regards to the right to be forgotten)… all of these things are putting more of an emphasis on data protection and journalism than before at the practical as well as the theoretical level. However, precisely how this will evolve, we just don’t know yet.

In the book you are publishing at the end of 2019, you say the European Data Protection Board has a valuable soft role to play. You are very much against coercion, underlining that the board has an educational role to play, among other things. Could you elaborate?

David Erdos: The European Data Protection Regulation is strongly based on recognizing that data protection is a fundamental right. At the same time, it has to balance this with other rights that come into the picture. Europe is committed to certain standards both in Strasbourg but, even more so, in Luxembourg, through the Court of Justice. Looking ahead, in order to implement this balancing process, there is a need to respond to the new issues coming to the fore, particularly as a result of new technology. That’s to say algorithmic decision-making in journalism, data journalism, drones and journalism, digital archives, and so on, where there is room for thinking about what the common norms might be are, what continuing divergences remain, etc. The Board can play a role in promoting legal certainty and incremental development of these norms while respecting national divergences. The very legitimacy of the regime here must respect the reality of divergent values and legislation. But the Board can play a soft role in bringing some of these issues together. It should, however, reject hard coercive actions because it is not well-placed for such a task here and would probably face a backlash if it tried. However, this is not to say there is no role for information sharing, guidance and pooling different practices in this area.

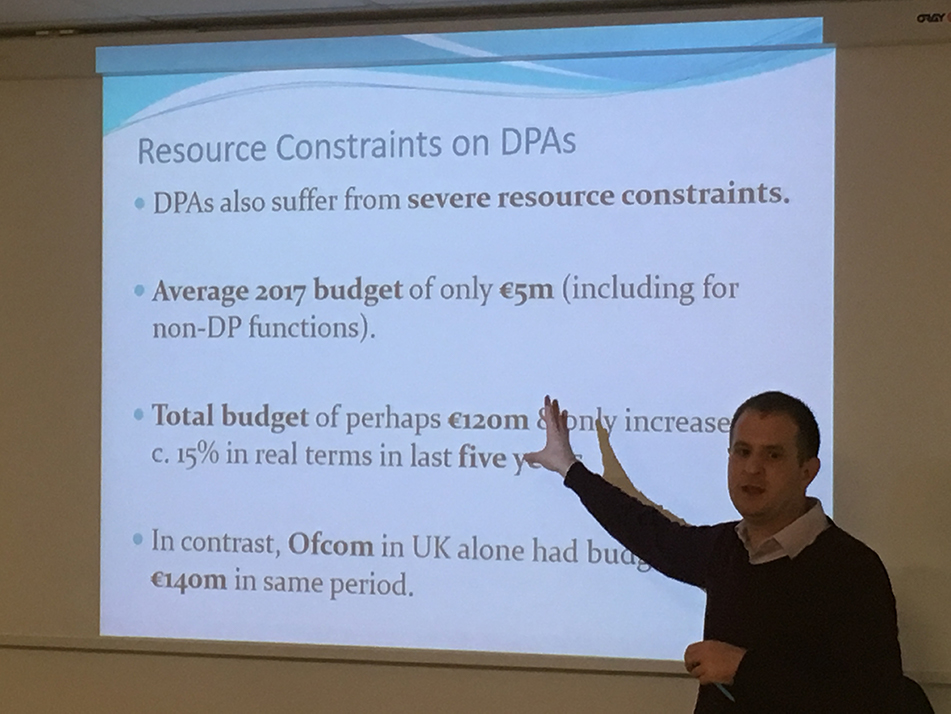

A question which returns regularly is resources. How can its scarcity (see photo above) evolve to answer the dimension of the data protection challenge?

David Erdos: The GDPR is clearer than previous instruments in stating that member states have a binding legal obligation to provide data protection authorities with the necessary resources. That is on the positive side of the equation. The negative side is that GDPR represents a significant step-up for many countries, and makes it much more challenging economically because so many legal obligations need to be implemented. Technology continues to move on in many ways, generally in tension with data protection standards. More and more data is being collected for more and more purposes, often more and more invidiously. This is the trend.

How do these factors balance up? It’s clear that countries are very reluctant to spend money in this area. And how precisely do you determine what DPAs actually need to do their job? It’s quite obvious that we don’t have appropriate levels of compliance and we need more commitment to this area. I am not very optimistic that things will change much. That’s because we’ve ended up in a situation where GDPR is putting in place more rules, more restrictions (some of which are quite problematic from the point of view of other rights and interests) But in the context where we are not even able to effectively implement old rules, this lands us in bigger problems in terms of gaps between the law in the books and these applied in reality.

You presented your research on GDPR and media regulation in front of fellow-specialists like the lawyer Hélène Lebon, the co-organizer of today’s talk, HEC assistant professor David Restrepo and HEC research fellow Delphine Dogot. What do you retain from this afternoon of exchange?

David Erdos: Oh, plenty! To begin with, I noted that there are challenges of compliance in several fields, not journalism alone. Another challenge is the extent to which data protection is actually being implemented by different EU member states. Then there is the challenge around the other ways media is inter-facing with data protection, notably tracking online cookies and compliance with e-privacy laws. That is a whole other can of worms.

Another take-home for me is the very interesting discussion we had about co-regulation, and not only in the journalistic sector. How do you promote co-regulation without creating opacity as to how standards are being set? How are standards being specified, applied or enforced? How do you ensure benefits from co-regulation, such as a role for self-regulation in terms of expertise and buy-in? How do you avoid creating a situation where there is a lack of clarity over accountability for minimum legal safeguards? These were some of the many issues which cropped up and which deserve further exploration.