Why is fame important?

Fame is not just positive press. It’s sheer attention which can be positive, negative and neutral attention in media. Obscurity is a cruel fate – there’s nothing harsher than seeing one’s work being ignored. Fame, instead, puts innovators on investors, collaborators, consumers’ radar. If no one hears about your work, then you cannot even begin to be considered for rewards. Being famous drastically increases the economic returns to your creativity. This is the case for famous artists, designers, and the new class of celebrity entrepreneurs who have monetized their fame into million dollar fortunes.

Innovators’ fame cannot be explained by their creativity but by having a diverse community of peers.

Being famous also allows greater career mobility. For example, famous B-list film actors (such as Ronald Reagan) successfully transition to great careers in other domains such as politics. In contrast, highly acclaimed but more obscure actors seldom experience that kind of mobility. At a more psychological level, in modern society, being written or talked about gives a reality and meaning to one’s endeavors. This has of course reached perverse levels in our hyper mediatized world. Nonetheless, fame is valuable both intrinsically and extrinsically. Unsurprisingly, some studies have found that scientists value fame over money. Despite our long-standing pre-occupation with fame, there’s still relatively little research on fame.

Thankfully, there’s an encouraging trend of more researchers studying it.

What motivated you to examine the fame of innovators as a function of the social structure they are embedded in?

Some innovators are household names while others remain relatively obscure. For example, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak co-founded a technology company that revolutionized personal computing. While Wozniak’s engineering talent was instrumental to the development of Apple products, he’s nowhere the kind of household name Jobs is. To take another example, consider the fame of two physicists, Richard Feynman and Murray Gell-Mann. Both men grew up in middle class families, received their training in elite American universities, made substantial contributions to their field and earned the highest recognition in their field - the Nobel prize in Physics. Yet, Feynman’s fame surpasses that of his contemporary Gellman.

Fame, like most forms of success, is better understood by examining the social structure in which these innovators are embedded.

These examples illustrate that innovators’ fame cannot be explained by their creativity or even accomplishments. Rather fame, like most forms of success, is better understood by examining the social structure in which these innovators are embedded. I model the social structure by the web of relationships, i.e. the network an innovator is embedded in.

Don’t we already know networks are important for success? What’s new?

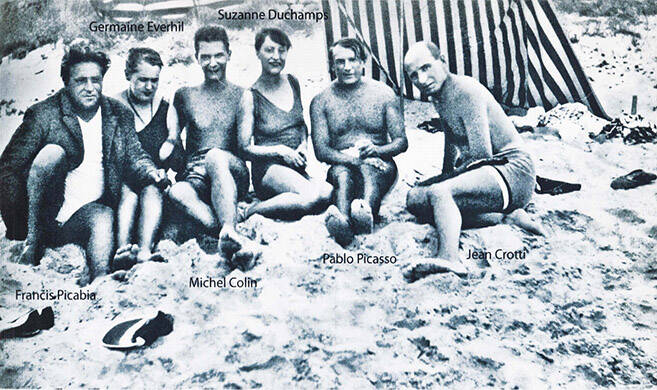

The most common view is that being connected to powerful people helps one’s career success. However, that’s not the whole story. To take two examples from our data – the artists Suzanne Duchamp and Vanessa Bell were both well connected. Both trained at elite art schools, both came from the elite families. Suzanne Duchamp was Marcel Duchamp’s sister and married to Jean Crotti, a well-established artist. Vanessa Bell was the writer Virginia Woolf’s sister and the daughter of the eminent literary critic Sir Leslie Stephen. Yet, we see considerable differences in the two artists’ fame - Duchamp is far less famous than Bell. The difference is striking especially given that Suzanne’s brother Marcel Duchamp was a star of the modern art world.

So simply being connected to a powerful people does not account for the difference in fame. Instead, our work shows that there are other elements of an innovator’s social structure, notably, the structure and composition of an innovator’s immediate peer network, that can account for these differences in fame.

How does an innovator’s peer network shape their fame?

We look at the structure and composition of an innovator’s peer network i.e. the peers she is connected to through informal ties. Such ties are often hard to observe but luckily, we were able to access some rare data that capture such informal ties. We focus on the extent to which innovator’s peers spans diverse social words. Two measures from social network analysis help represent the extent to which innovators span diverse social worlds.

Structural diversity, more commonly referred to as brokerage, captures the extent to which an innovator’s peers are disconnected from each other. If most of my friends don’t know each other, then they represent very different worlds. In such situations, I span very diverse social worlds. In contrast, I could be part of a clique, where all my friends know each other.

Compositional diversity captures the extent to which an innovator’s peers network comprises people from similar or diverse backgrounds. For example, innovators whose peers are from different nationalities have greater compositional diversity in their immediate peer network than innovators whose peers are from the same country.

Structural diversity captures the extent to which an innovator’s peers are disconnected from each other, whereas compositional diversity captures the extent to which an innovator’s peer network comprises people from similar or diverse backgrounds.

Considerable research suggests that spanning diverse social worlds is advantageous, especially for creativity. Such diversity gives access to new and different ideas, which can spur an individual’s creativity and, thereby, help their success. This view has held considerable sway. However, most prior research proxies creativity with measures of success. As a result, it has been hard to disentangle whether diverse social worlds shape success through creativity or independent of it. Our research disentangles these two paths.

You differentiate whether networks shape fame directly or through creativity. Why is it important to disentangle these paths?

The two paths help us understand the channels through which networks shape success. Do networks help promote creative products or the actual creativity of the products?

Moreover, there’s a lot of talk about the importance of creativity. This is particularly true of creative fields like science or arts which idealize creativity. We naturally assume that anything that augments creativity will lead to creative success, in this case fame. But this has been implicitly assumed and not tested. Studies typically conflate measures of creativity with those of creative success such as awards. Even expert evaluations reflect a form of institutional approval, and hence a form of creative success. We used some state-of-the-art methods in deep learning to measure objective creativity. Examining whether networks shape fame through the channel of creativity helps us understand whether markets actually reward creativity. Or is success a reproduction of some network structures where one occupies a favorable position?

In which context do you examine these questions?

I use the early 20th century modern art market as a context. We were able to access rare data on the informal ties of a set of pioneers of abstract artists through the Museum of Modern Art.

How do you measure an artist’s creativity?

We use two measures – expert evaluations of the artists’ work and a computational measure using an image recognition algorithm. The latter is a deep learning tool – a convolutional neural net that we use to represent each painting as a vector. Once we have a vector representation of the paintings, we compute distances between paintings. We use these distances as a representation of the artist’s creativity.

We find a statistically meaningful correlation between the expert and the computational measure. Apart from that, we demonstrate through several examples that the measure is able to distinguish between the creativity of paintings from the same painter as well as from different painters. Also, the measure is not biased by the artist’s fame and we were able to apply it to thousands of paintings created by the artists in our sample.

In this respect, the measure is both more objective and consistent relative to expert evaluations. Of course, the measure can be improved. Our hope is that future will explore refinements of this measure.

What do you find? Does being part of diverse social worlds help an artist’s creativity and, in turn, her fame?

We find that diverse networks have a direct effect on fame, but not through the channel of creativity. This result holds true for both the expert and computational measure of creativity.

We find that being part of more diverse social worlds helps artists’ fame – artists with greater national diversity in their peer network are more famous. In addition, within the informal peer network, we find that artists with greater structure diversity i.e. those with friends who are disconnected from each other, are more famous.

Don’t art worlds tend to be cliquish?

Yes, indeed. The result is particularly interesting given the cliquishness within the art world. This is the case for many fields – academia, fashion, etc. where people tend to be clubby and want to be in homogenous circles of friends. However, our results suggest that at least within our circle of informal relationships, having greater diversity helps. Cosmopolitanism rather than cliquishness within informal relationships is more helpful for fame.

Cosmopolitanism rather than cliquishness within informal relationships is more helpful for fame.

We do find evidence for cliquishness helping fame in the artists’ institutional network, which is the network formed from co-exhibiting with other artists.

In your data, did you worry that an artist’s prior fame or prior creativity could be influencing their network?

Yes, reverse causality is a concern. We did several things to address this. One of them is morbid - we used artists’ peers’ deaths in World War I as an exogenous shock to the network structural diversity. Artists whose peers died in WWI experienced an exogenous decrease in their structural diversity. We find that this decrease in structural diversity is also associated with a decrease in fame. We used other statistical tools such as panel data fixed effects and structural equation modeling to further address some of these concerns.

So networks do not shape fame through creativity. Does that mean that creativity does not matter? That sounds depressing.

Indeed, the result is striking given that our context is the art market where creativity is deeply valorized. Our results suggest that there’s a disconnect between purported values and what’s actually rewarded.

It is a disquieting result. While there’s a cynical intuition that success is not about work but about connection, our result is a much more refined version of that. First, it is not simply about being connected to powerful people. Rather, the more famous artists had more diverse networks.

Existing research suggests that the link between network diversity and creative success is creativity. But we don’t find evidence for that. Our hope is that the result will provoke further exploration into how different types of network structures shape different aspects of creative careers. Our model and methods also provide a systematic framework that can be applied to other contexts to disentangle the role of social structure and creativity in shaping success. Finally, recognizing the disconnect may help us better design creative markets to reward creativity, that is, if we truly want to reward it.

On the optimistic side, our results should encourage people to seek out more diversity in their network. Of course, connecting with different groups and communities can be extremely personally enriching. It is a great way to get out of one’s echo chamber and limited world view. But in case one needs an extrinsic motivation, having a diverse group of friends can actually help your career, though not necessarily by making you more creative.

How did you choose this context of modern art?

I think, it chose me. When I was a doctoral student at Columbia University, I was asked to help curators at the MoMA create a network graph among pioneers of abstraction for an exhibition. I worked with the MoMA team for several months to construct the graph – it was an amazing experience. The network was used as part of the Inventing Abstraction Exhibition which went on to win several awards.

After the exhibition, I found myself frequently in the basement of Avery library, the main art library at Columbia, pouring over volumes of artists’ biographies. Soon I was checking-out stacks of art history texts and crowding out our bookshelves at home. I was hooked. I was fascinated by the parallels between art and the development of science and new technologies. Like many new scientific ideas and technologies, these artists innovations encountered a lot of resistance. Their work was derided as gimmicky and as an insult to tradition. Yet, their work changed the very idea of what is art. They redefined their field – they revolutionized the world. I was fascinated by the informal and rich interactions that facilitated such a paradigmatic shift. It reminded me of classic sociological work on innovation such as AnnaLee Saxenian’s “Regional Advantage”, which finds the same kind of rich interactions were important for the growth of Silicon Valley. I could go on…but in short, the context consumed me.

Can your results be extended to other contexts?

Yes, we expect our methods and theory can be applied a host of other contexts. Given that our context is one where creativity is a deeply cherished value, our results can be seen as a conservative evidence for the absence of creativity as a link between networks and fame. We expect that the results will be stronger in other contexts such as science, technology and entrepreneurship. These contexts also offer opportunities for refining our model. For instance, unlike art, technological innovations also have to serve a more utilitarian purpose. Also technological innovations can be mass produced. These features of a market may produce interesting variations. Finally, our context pre-dates the birth of social media which has altered the dynamics of fame.