Dare HEC Media Hub

Can Leaders Still Rely on the Old Global Playbook?

10 minutes

Jeremy Ghez

As globalization fractures into new alliances and shifting blocs, business leaders must rethink risk, opportunity, and a…

As globalization fractures into new alliances and shifting blocs, business leaders must rethink risk, opportunity, and alignment. Why does the cognitive map of globalization never …

Insights You Need

In an era of rising inequality and inflation shocks, companies are becoming frontline actors in shaping social justice.

11 minutes

Marieke Huysentruyt

Noticing is a leadership skill. Van Gogh makes it unavoidable, and Daniel Newark turns it into practice. While most leadership programs emphasize decisive action, clear comm…

Daniel Newark

Some encounters change destinies. Keep your mind open.

Inspiring voices

94 minutes

Leaders speaking openly about their vulnerability

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

Stories

What the Homeless Taught Us About Dignity

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

Jean-Marc Semoulin: Trust as a Political Act

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

HEC Startups

Think sharper. Grasp what matters. Solve better.

Reskill Masterclass

32 minutes

How Firms Value Sales Career Paths?

Dominique Rouziès

Knowledge

Trust Is the Invisible Infrastructure of Prosperous Societies

Marieke Huysentruyt, Yann Algan

5 mn

Is Loneliness the Most Overlooked Economic Risk of Our Time?

Marieke Huysentruyt, Yann Algan

Decoding

Enough talk. Join the doers. Make change happen.

Students POV

HEC Startups

Features

April 2025

AI Technology: On a Razor's Edge?

AI challenges creativity, governance, jobs, and trust, raising urgent questions across every sector.

January 2025

Saving Lives in Intensive Care Thanks to AI

Julien Grand-Clément

AI Accuracy Isn’t Enough: Fairness Is Now Essential

Christophe Pérignon

AI and Sovereignty: The Geopolitical Power of Submarine Cables

Olivier Chatain, Jeremy Ghez

Growth or Human Ties

The Selection By

Isaline Rohmer

Isaline Rohmer is a consultant and member of the Omnicité cooperative. She coordinates a research program for HEC Paris on social entreprene…

December 1st, 2025

Podcasts

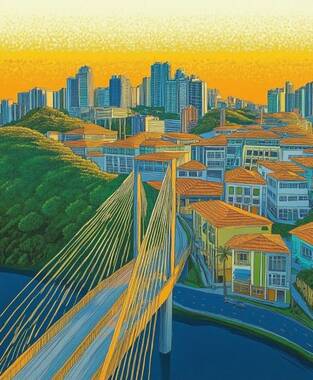

Voices Creating New Narratives and Shaping the Future of Megacities

Inside São Paulo: Building Bridges Toward Shared Prosperity

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

41 minutes

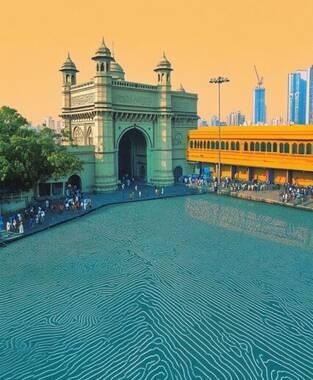

Inside Mumbai: Bridging Divides in a City of Extremes

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

Inside Cairo: A Layered City Where Past and Future Intersect

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

38 minutes

Inside Kinshasa: The Forces Powering Africa's Largest Urban Future

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

27 minutes

HEC researchers unpack their latest findings on real-world challenges

How Platform Architecture and Oscar Nominations Influence Our Choices

Michelangelo Rossi

32 minutes

Videos

Videos that break down big ideas in minutes

Leading figures with ideas that matter to elevate the debate

94 minutes

Leaders speaking openly about their vulnerability

HEC Paris Sustainability & Organizations Institute

Live masterclasses to learn new skills and grow professionally

Students’ perspectives on what matters today and what drives them

For curious minds seeking research-based insights and inspiring stories that help make sense of a world in transition, and unlock solutions within a purpose-driven community.